The most famous statue in the world still has the power to inspire

What tends to strike viewers when they first see Michelangelo’s David is its size: it stands at over 5 metres from top to bottom, so that when you’re standing beneath it, your only choice is to look upwards.

In this way, the statue looms. It rises like a column, dominating the environment of the Galleria dell’Accademia in Florence where it is currently housed.

Then, after a few more moments of looking, some people begin to sense that David’s proportions are a little off-kilter. For a heroic statue, his hips and legs are curiously narrow, whilst his neck and head are weighty and substantial.

The meddling of proportions was intentional. Michelangelo carved the statue to meet its original commission, to stand along the roofline of the east end of Florence Cathedral alongside a series of other prophets. As such, the statue would have been seen from street level; Michelangelo’s solution was to follow classical methods by enlarging the proportions upwards so that from below everything would look correct.

Yet there’s no escaping the fact that this is a sublime work from the hands of an exceptional artist. And it isn’t only art history that confers greatness on this marble sculpture: Michelangelo’s contemporaries thought it was far too good to place high on the roof of the cathedral and instead placed it in the busiest square of the city. In the Piazza della Signoria, where a copy still stands, it could hardly have been more prominent.

And then there is Giorgio Vasari’s famously gushing judgement: “Anyone who has seen Michelangelo’s David has no need to see anything else by another sculptor, living or dead.” Praise indeed from the first historian of art…

The young hero

The statue depicts the youthful David, the future king of Israel. Over his left shoulder he holds a slingshot with which he has (or is about to) fling a rock at Goliath, the Philistine giant. The rock will hit Goliath in the centre of his forehead and Goliath will fall to the ground, whereupon David will cut off his head to finish the fight.

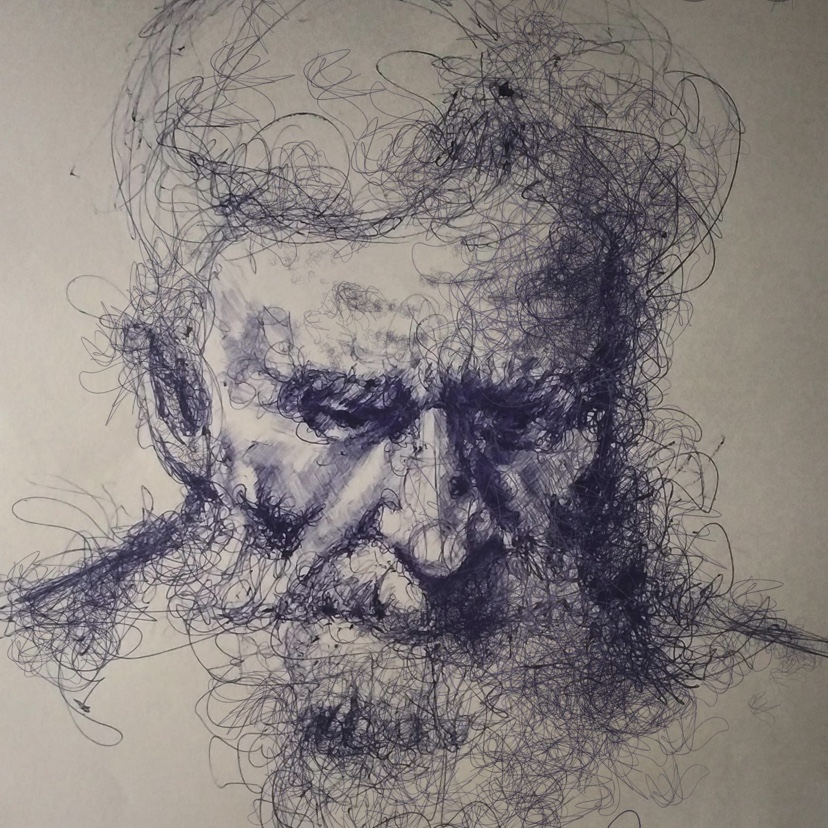

Despite the valiant narrative, Michelangelo has given David a decidedly brooding posture. His distant gaze, and the way his arm hangs impassively at his side, seem to tip the scales away from heroic vigour towards a more introspective poise.

What we are looking at, then, is David in a moment of contemplation. Most interpretations conclude that the sculpture shows David before his battle with Goliath, sizing up his opponent. The furrowed brow, the thick stare, and the veins bulging from his lowered right hand, make the case for a man calmly sizing up his enemy.

Yet I always found David to be a lonely figure. He appears somewhat companionless, an outsider even. I take this ambiguity as part of the statue’s meaning. For this is really a portrait of a noble figure, intended to represent the psychological balance of the whole man rather than a moment in a narrative drama. David the warrior is easy to glorify, but David the honourable, worthy, distinguished yet also real, vulnerable, contemplative, is a much more complex prospect. And works of art that aim at such complexity tend to last the test of time.

The hardest block of marble

The statue of David was also an opportunity for the young Michelangelo to display his unprecedented skills as a sculptor. He was 26 at the time of the work’s commission, having just returned to Florence in 1501 after a period working in Rome. Famously, the statue was carved from a single piece of Carrara marble, a huge block of stone that had been rejected or abandoned by at least two other artists prior to Michelangelo’s undertaking.

The marble block had languished untouched for over a quarter of a century. Another Florentine sculptor by the name of Agostino di Duccio had been assigned the task originally. Beginning in 1464, Duccio wrestled with the massive piece of stone, getting as far as marking out the legs, feet and torso, perhaps even chiselling a hole between the legs. Ten years later another sculptor, Antonio Rossellino, was commissioned to take over from Agostino, who seems to have left the project midway. Rossellino didn’t last long either, and the unfinished sculpture remained untouched for the next 26 years.

The block that Michelangelo inherited was in rough condition. In September 1501, the church authorities settled on the 26-year-old as the next to try his hand at the imposing mass of marble. Michelangelo had recently proved his worth by carving the emotionally powerful Pietà, showing the body of Jesus on the lap of his mother Mary after the Crucifixion. By April 1504, the statue of David was complete.

David’s languid pose

How does a person look when they are standing upright? In Egyptian sculpture, the answer to this question emphasised the natural symmetry of the human body. Egyptian sculpture was front-on, with level shoulders, symmetrical arms and hips.

These traits passed onto early Greek sculpture. Yet one of the most interesting aspects of the development of sculpture in Greece was the inception of a new type of posture. Known since the Renaissance as contrapposto, this nuanced but fundamental invention offered a turning point in the course of naturalistic representation.

The contrapposto technique can be readily seen in this sculpture, the so-called “Spear Carrier” attributed to the Greek sculptor Polykleitos. The image shown below is a marble Roman copy made after the bronze original, which has been subsequently lost.

Notice the distribution of weight, being borne on one leg whilst the other is relaxed. The deliberate asymmetry of the legs instigates movement throughout the rest of the body. The hips tilt, thereby causing the torso to squeeze on one side and open on the other. In this way, broader symmetry gives way to a more flexible pose overall; one arm is raised (holding the missing spear) whilst the other hangs down to one side. The head is turned as if gazing into the distance. The sculpture can be viewed from many angles — seen “in the round” — and still deliver its full impact.

During the Italian Renaissance, this classical pose was explicitly revived. Taking inspiration from Roman sculptures that were being unearthed across Italy at the time, Italian sculptors reawakened and expanded the method. Indeed, contrapposto is an Italian word meaning “counterpoise” and was coined in the time of the Renaissance.

Michelangelo’s sculpture of David is probably the most famous statue that makes use of contrapposto. David’s left leg is emphatically relaxed, adding further weight onto the right leg. The important tilt of the hips is there; along with it the right arm hangs long, almost heavily, so that the entire torso and shoulders lean to one side. In all, the arrangement is asymmetrical yet harmonised, yielding a gentle S-shape in the body to give a sense of serene contemplation predicated on muscular strength.

A Florentine emblem

With its imposing naturalism and understated sense of self-confidence, the figure of David soon began to attract attention. A 30-strong committee gathered to reconsider its purpose — including venerable artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli and Giuliano da Sangallo. Given that the six-tonne statue was probably too heavy to lift to the roof of the cathedral, the committee considered several alternative locations, with the Piazza della Signoria — the political heart of Florence — eventually selected.

First, the great statue had to be moved the half-mile from Michelangelo’s workshop behind Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral to the piazza. The event was captured in a diary entry from a local herbalist Luca Landucci:

“It was midnight, May 14th, and the Giant was taken out of the workshop. They even had to tear down the archway, so huge he was. Forty men were pushing the large wooden cart where David stood protected by ropes, sliding it through town on trunks. The Giant eventually got to Signoria Square on June 8th 1504, where it was installed next to the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio, replacing Donatello’s bronze sculpture of Judith and Holofernes”.

The statue soon became a symbol of the Republican ideals of Florence. Fearless, sovereign and self-sufficient, it seemed to say so much about the independent spirit of the city.

It remained in the Piazza della Signoria until 1873, when it was moved into the Galleria dell’Accademia to protect it from weathering. A replica was placed in the Piazza della Signoria in 1910.