Why Caravaggio’s paintings were rejected by the Christian patrons

Caravaggio was a famous painter in the 16th century. His chiaroscuro paintings narrated high drama, acute realism, and minute detailing.

But have you ever noticed the dirty feet in Caravaggio’s paintings?

Saint Matthew and the Angel, Crucifixion of Saint Peter, Madonna of the Rosary, and several others reflects the famous “dirty feet”.

The dirty feet got affixed to his art form, personality, and portrayed the catholic pauperism beliefs that were opposed by the Catholic Reformation.

Caravaggio’s early life and initial paintings

The baroque painter was born in Milan where he was baptized. His childhood and education were spent in catholic pauperism beliefs in the spirit of St. Charles Borromeo.

He did his initial training under Simone Peterzano and left for Rome from Milan in 1592.

Caravaggio’s naturalistic and unorthodox painting skills caught eyeballs of the Roman Catholic patrons during the counter-reformation in Rome.

The Boy Bitten by a Lizard in the National Gallery London was painted by him during his beginnings in Rome. This painting revealed the authenticity and realism; he painted the model with dirty fingernails and gave surmountable importance to the detailing of the inanimate objects like the sprig of jasmine inside the glass vase.

Caravaggio’s Paintings with Dirty Feet

Saint Matthew and the Angel

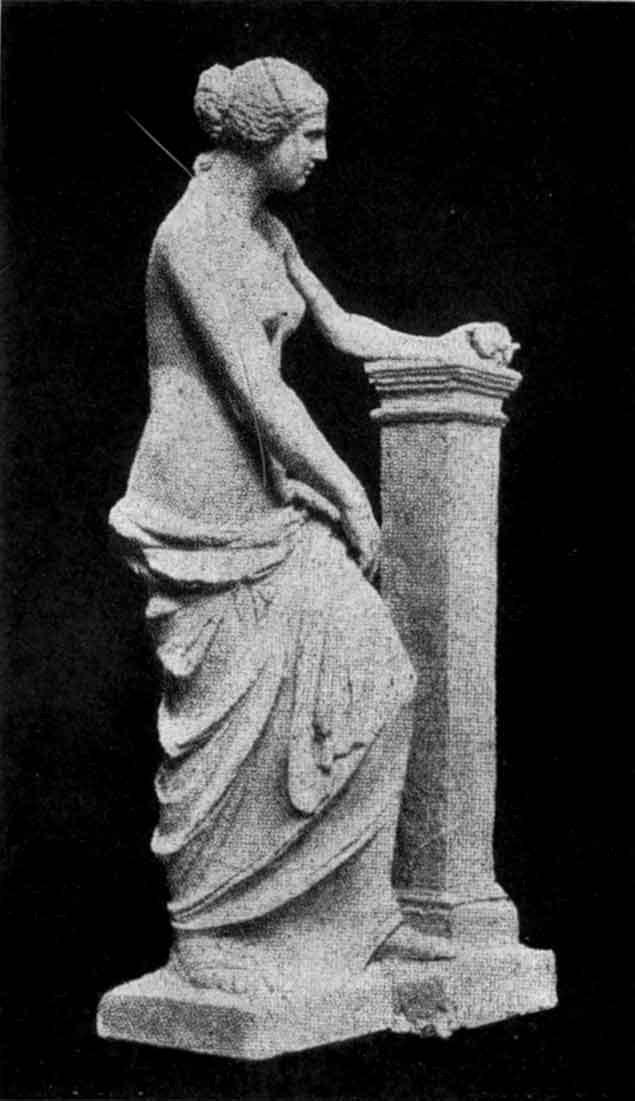

Note the naked feet and impoverished dressing in the left image.

In 1599, he was contracted by the Contarelli Chapel to decorate the Church with the paintings of the Evangelist Saint Matthew.

His first version of Saint Matthew and the Angel was rejected by the Church patrons.

The dirty feet of the Saint and impoverished nature did not match the idealization of their beloved Saint Matthew. The Church leaders found it really crude and could not see the image of a poor peasant depicting as their Evangelist.

And so, he had to paint the second version The Inspiration of Saint Matthew depicting a more glorified and reverent image of the master that was accepted by the Church officials.

The Crucifixion of Peter

When Peter was crucified, he asked to be turned upside down to be the opposite of Jesus’ crucifixion. This painting too depicted the dirty feet of the man pushing up the cross.

Why the paintings were rejected by Church

The Counter-Reformation Popes in Rome opposed the ideology of pauperism. The Church patrons thought that all the poor; and especially the beggars, held no interest in the church reforms and were considered as ‘ignorant of Christian truth’.

According to them, the poor people were seen as sinners or criminals.

Therefore, the Church outrightly rejected paintings with dirty feet by Caravaggio at first look and wanted to promote more glorified images of their Saints.

Caravaggio’s school of thought was inspired by pauperism. And, so the naked and dirty feet of Caravaggio’s saints were the feet of those who believed that Jesus, the son of God was “made man” and lived in poverty.

His compositions were being asked to alter by the Church to suit the desires of the patrons during that era. But Caravaggio’s sense of authenticity, the rawness of human existence is still perfectly preserved in the Augustinian churches of Rome